by Nancy E. Brune, Ph.D.

Strengthening Community Policing Through Data?

Last month, officers from the Sacramento Police Department shot and killed Stephon Clark, an unarmed young adult African-American male in his grandmother’s backyard “during a vandalism investigation.” This incident marks another in a series of officer-involved shootings and incidents of police brutality in predominantly minority communities that “have exposed rifts in the relationships between local police and the communities they protect and serve” in recent years. The national conversation and concomitant emotion surrounding these events have transcended matters of law and justice.

Collectively, these events have prompted political, community, and law enforcement leaders locally, and across the country, to examine current policies and procedures, particularly as they relate to community policing. Community policing is defined as the promotion of organizational strategies that support crime prevention, community problem-solving, and strong law enforcement-community partnerships.

In December 2014, President Obama launched the Task Force on 21st Century Policing to study approaches to strengthen law enforcement and community relations, while at the same time enhancing public safety. That Task Force developed 59 concrete and specific recommendations in six core areas:

- Building Trust and Legitimacy

- Policy and Oversight

- Technology and Social Media

- Community Policing and Crime Reduction

- Training and Education, and

- Officer Safety and Wellness

Many of these recommendations emphasized the importance of high-quality and effective training, which will prepare officers to respond to the wide range of challenges they face (e.g., evolving technologies, immigration, changing laws, a growing mental health crisis, etc.) as they interact with the community.

However, the Task Force also emphasized the (often overlooked) importance of data as a means of building public trust and ultimately improving relationships between law enforcement agencies and the greater community. The Task Force wrote, “Data collection, supervision, and accountability are also part of a comprehensive systemic approach to keeping everyone safe and protecting the rights of all involved during police encounters.” The report stated, “To embrace a culture of transparency, law enforcement agencies should make all department policies available for public review and regularly post on the department’s website information about stops, summonses, arrests, reported crime, and other law enforcement data aggregated by demographics.” The Task Force also recommended that, “Law enforcement agencies should have comprehensive policies on the use of force that include training, investigations, prosecutions, data collection, and information sharing. These policies must be clear, concise, and openly available for public inspection.”

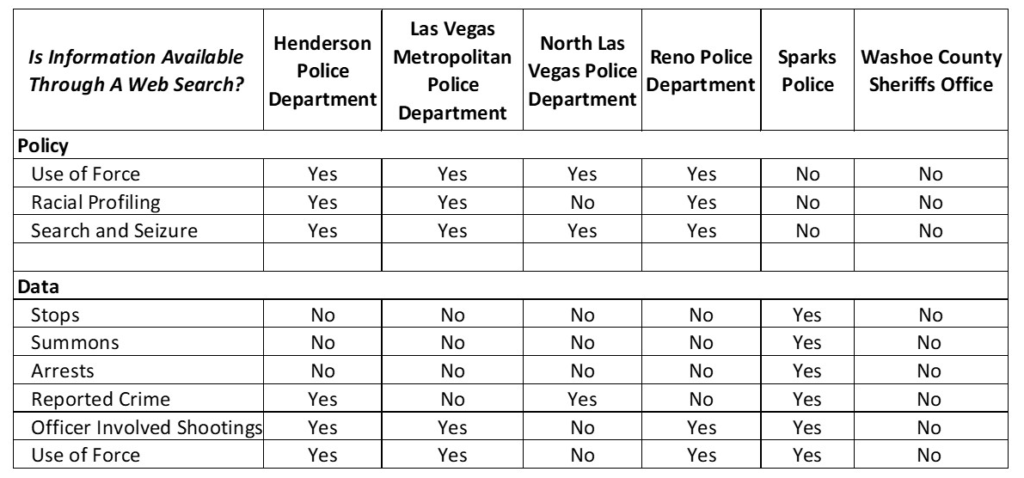

A brief scan of a selection of law enforcement agencies in Nevada reveals that there is variation in the degree to which law enforcement agencies publish data and information on their policies (see Table 1). Both Sparks Police and the Henderson Police Department participate in the Police Data Initiative, which is a “community of practice that includes leading law enforcement agencies, technologists, and researchers committed to improving the relationship between citizens and police at the local level through the use of data to increase transparency, build community trust, and strengthen accountability.” Several law enforcement agencies publish information on use of force and officer-involved shootings but do not release information on “stops, summonses, arrests, reported crime, and other law enforcement data aggregated by demographics.” The Reno Police Department publishes information about officer-involved shootings and use-of-force incidents in its annual Internal Affairs report, which is published on the Department’s website. Some law enforcement agencies publish their key policies in the officer manual or handbook. Others, like Reno Police Department and Las Vegas Metropolitan Police Department, publish specific policies on their respective websites. In contrast, several of the law enforcement agencies do not publicly report key policies or accountability measures. While not presented here, we observed that the school district police in the Silver State’s two urban school districts (Clark County and Washoe County) do not publish any data on their websites about school discipline or student referrals.

The consistent collection and reporting of data and accountability measures take time and require fiscal and administrative resources. However, as the Task Force suggests, the collection and publication of data strengthens transparency and can help build trust and legitimacy among the public with respect to law enforcement agencies.

Researchers Tom Tyler, Phillip Goff, and Robert MacCoun found that “when people feel the police have legitimacy, they are more likely to follow the law to comply with officers’ directives and to co-police neighborhoods by reporting crimes, identifying criminals, and acting as witnesses during trials. People’s perception of police legitimacy is most greatly influenced by their sense that the police make decisions fairly and treat people fairly.” Investing in the collection and publication of data can help conversations and provide clarity when unexpected events test the fabric of relationships between law enforcement agencies and the community.

Table 1. Public Reporting by Selected Law Enforcement Agencies on Key Accountability Measures and Policies