Nevada’s frequently bleak educational outcomes are often compounded when a student comes from an at-risk population. These populations can include students with disabilities, students from low-income families, students in the foster care system, and students who do not perform at grade level.

Recognizing this problem, the Nevada Legislature has crafted a series of bills aimed at providing increased supports and services to children in the state’s most vulnerable subgroups. This post highlights the bills that seek to improve outcomes for at-risk youth in our state and discusses our research on why these bills are a good idea or contain good ideas for improving educational quality in Nevada.

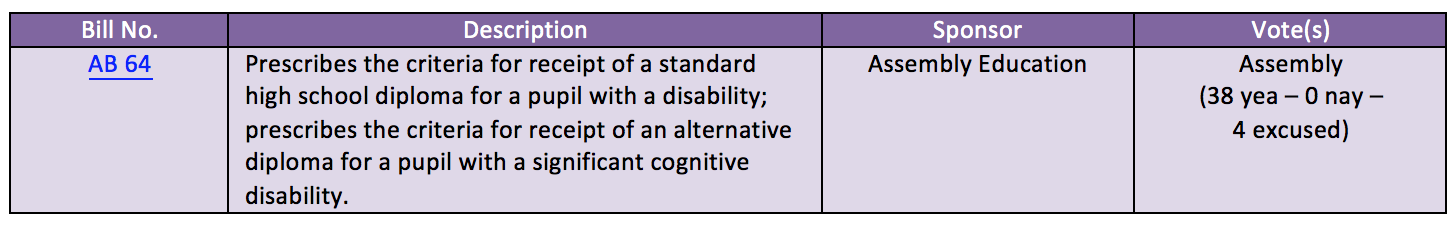

Assembly Bill 64 (Read the Guinn Center’s policy note, “Graduation Requirements for Students with Disabilities.”)

In 2016, the Guinn Center assessed how well Nevada has provided post-secondary pathways for our transition age students with disabilities. We found that the pathways in Nevada to prepare successfully students with intellectual disabilities for post-secondary opportunities are quite limited – meaning that there are significant gaps and barriers preventing students with disabilities for life beyond high school. Our findings appeared our report, Pathways to Nowhere: Post-secondary Transitions for Students with Disabilities. (See here for companion video).

Almost 12 percent of Nevada’s K-12 public school enrollment are students participating in an Individualized Education Program (IEP) and are designated as special education students under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). Educational outcomes for our students with disabilities are bleak. In 2014-2015, only 29 percent of students with disabilities in Nevada graduated, compared to a graduation rate of 71 percent for all students in Nevada. This achievement gap of 42.3 points was the second biggest in the United States. In Clark County School District, the 2015 graduation rate for students with disabilities was 28 percent. In Washoe County School District, the 2015 graduation rate for students with disabilities was 29 percent. Post-secondary outcomes are just as dismal. In 2014, only 24 percent of Nevada students with disabilities enrolled in higher education within one year after leaving high school. Only 54 percent were enrolled in higher education or competitively employed within one year of leaving high school. Only 14 percent received a bachelor’s degree or higher.

One of the reasons that the graduation rate for students with disabilities is alarmingly low is because the Silver State offers a second pathway – namely the adjusted diploma. However, 40 states in the country have eliminated a different pathway – e.g., an adjusted diploma – for students with disabilities.

In 2015-2016, 883 students with disabilities received a standard diploma, reflecting a graduation rate of 21.5 percent. And 890 adjusted diplomas were issued. In several counties, more adjusted diplomas were awarded than standard diplomas.

Unfortunately, the adjusted diploma limits post-secondary opportunities for students with disabilities. An adjusted diploma is not the equivalent of a high school diploma and students who graduate with an adjusted diploma cannot enlist in some branches of the military or apply for Federal financial aid. Additionally, some employers in Nevada will not recognize an adjusted diploma for admittance into their training programs.

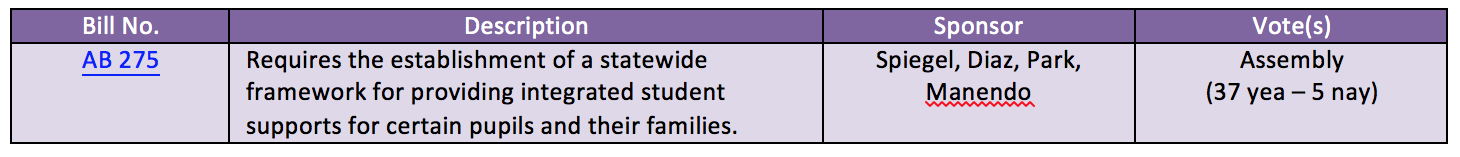

Assembly Bill 275 (Read the Guinn Center’s policy note, “The Importance of Integrated Student Supports for Student Success.”)

Earlier this year, the Kenny Guinn Center for Policy Priorities published a policy brief, “A New Nevada: Early Childhood Education and Literacy Interventions in Nevada’s K-12 Public Schools.” Based on our research, we would like to voice our support for efforts, as embodied in Assembly Bill 275, to establish of a framework for delivering and evaluating integrated student supports for certain students and their families. The intent of AB 275 speaks to two of the key findings in our report: (1) that students perform better in schools when their other, non-academic needs are being addressed, and (2) increased accountability m easures and reporting requirements can help shape best practices and inform future policy decisions.

Nearly 22 percent of children in Nevada live in poverty (Casey Foundation). We believe that addressing the needs of these children, as well as the hundreds of thousands of others who come from high-need, at-risk communities around our state, through integrated supports can help prepare these children to succeed in school and that they will be better prepared to participate in the New Nevada Workforce.

Correlation between Wraparound Services in Schools and Increased Student Achievement

Research indicates that a child is better prepared to take on rigorous academic pursuits when the child’s other more basic needs, such as food and shelter, are met. In our state, there is already early evidence showing that students are better equipped to learn when schools provide wraparound support services.

Victory Schools

Victory Schools provide additional academic programming and wraparound services targeted toward their students and families. Victory Schools have the highest rates of Free and Reduced Price lunch (FRL) students in the state, and they are also typically among the lowest-rated schools on the Nevada State Performance Framework (NSPF). Nearly half of the additional funds for Victory schools must be used toward one or more of the following services that provide non-academic assistance to students and their families: (1) evidence-based social, psychological or health care services to pupils and their families, including, without limitation, wrap-around services, (2) programs and services designed to engage parents and families, (3) programs to improve school climate and culture, and/or (4) evidence-based programs and services designed to meet the needs of pupils who attend the school, as determined using the needs assessment.

As of May 2016, early results from Victory Schools showed mostly positive results, with increases in literacy proficiency rates across most schools.[1] These results reflect a smaller achievement gap by nearly 2 percent than the difference in reading proficiency between all FRL students in the state and these same schools in 2013-2014, the closest school year for which data is available and prior to the creation of the Victory School program. These small gaps in proficiency suggest that the literacy interventions in place in Victory Schools are working.

Communities in Schools

Communities in Schools (CIS) is a national nonprofit that operates in Nevada, and provides services in northeastern Nevada (Elko), northwestern Nevada (Reno), and southern Nevada (Las Vegas). Communities in Schools brings together all sectors of the community – from businesses and other nonprofits to government agencies and faith-based organizations – to provide the resources that help students to graduate on time, prepared for college, career and life.

Among the services CIS offers is the CIS Academy, in partnership with the Clark and Elko County School Districts. The CIS Academy is an in-school, dropout prevention program that assists at-risk youth at targeted schools with successfully starting and completing high school. CIS Academy teachers use tutoring and credit redemption programs to help students catch up academically. Career exploration and service-learning experiences help students develop real-life skills and plan for the future.

CIS Academy students enrolled in the fully scaled program in 2012-13 made the following gains:

- 93 percent of students decreased the number of out-of-school suspension days

- 90 percent of students decreased the number of days they spent in in-school suspension

- 85 percent of 12th grade students graduated

- 68 percent of students increased their grade point average, and

- 65 percent of students maintained or increased the number of credits earned.

CIS conducts a needs assessment to identify and help develop a plan for each student. CIS then works with partners to provide integrated student supports to students (and their families). CSI then monitors and evaluates student outcomes.

Increased Accountability Measures Can Drive Decision-Making

AB275 calls for school districts to “(1) conduct annually a needs assessment to identify the academic and nonacademic supports needed within the district or charter school; (2) ensure that mechanisms for data-driven decision-making are in place and the academic progress of pupils for whom integrated student supports have been provided is tracked; and (3) ensure integration and coordination between providers of integrated student support services.”

Our research shows that these measures are a critical component of ensuring that information about best practices is disseminated and implemented across all school campus and that funds are being used appropriately to provide high-quality service delivery. Pre-K programs in Nevada that are funded through federal grants are required to participate in both annual and longitudinal evaluations, comply with NDE data reporting requirements and other assessments, and maintain health and safety standards.

Alignment with Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA)

Under the federal Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA), Title I schools across the U.S. and in Nevada are permitted to apply Title I funding toward integrated student services. Too many schools focus only on what happens at the school site, rather than considering and addressing the education experiences before and after child sets foot in that building. This siloed approach makes it more challenging to meet the needs of every child, and offers the risk of perverse incentives and shortcuts at school sites that lack strong leadership. AB 275 can help strengthen the accountability measures for the use of these funds for wraparound service delivery at schools.

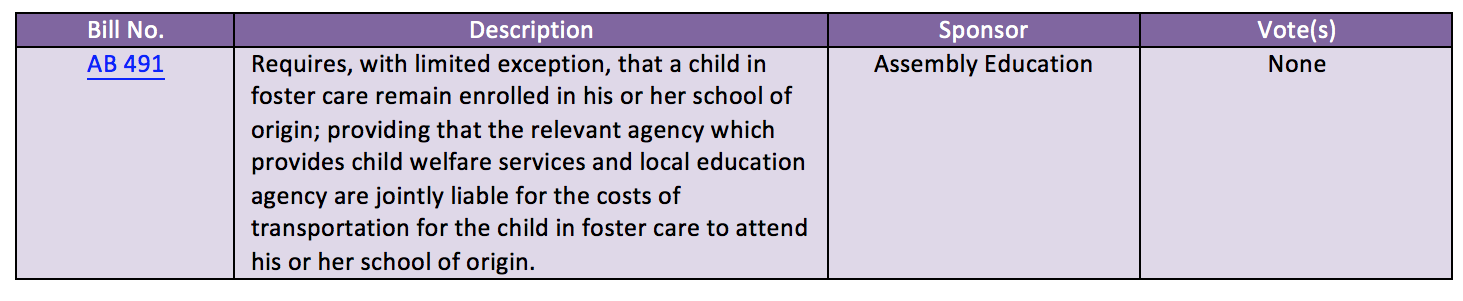

Assembly Bill 491

In September 2016, the Guinn Center for Policy Priorities, in collaboration with the Public Education Subcommittee of the Blue Ribbon for Kids Commission convened by the Nevada Supreme Court, published a policy brief, “At the Tipping Point: Educational Outcomes of Youth in Foster Care in Clark County School District.” This report found that children in foster care face considerable obstacles that can hamper their educational success, including:

- An increased likelihood of dropping out of school. Children in foster care are less likely than their non-foster care peers to obtain a high school diploma or to attend college. By most estimates, the graduation rate for students in foster care is at least ten percentage points lower than other students. Students in foster care also have higher rates of absenteeism, tardiness, and truancy. In Clark County School District, for example, the graduation rate for foster youth in Clark County was 47.5 percent in 2015, and the non-foster graduation rate was 83.9 percent.

- Lower scores on standardized tests and poor grades. One study found that children placed in foster care scored 16 to 20 percent below non-foster children on state standardized tests. Children in foster care are more likely to have to repeat a grade and are less likely to perform at grade level. For children in foster care in Clark County School District, 21.0 percent of their total grades were F’s in 2015-2016, compared to only 6.0 percent for non-foster care students.

- More behavior problems in schools and more likely to be assigned to special education classes. Twenty five percent of children in foster care in Clark County School district receive special education services. Many of these children have been victims of trauma, which can negatively affect their development and academic success.

A major contributor to these troubling outcomes is the transiency rate for children in foster care. Research finds that students in foster care move schools at least once or twice a year, and by the time they age out of the system, over one-third are likely to have experienced five or more school moves. For instance, the 2015 Youth at Risk of Homelessness, administered by the Clark County Department of Family Services, found that the average number of placements among surveyed youth, including youth in foster care, was ten. Youth in foster care are estimated to lose four to six months of academic progress with each change in school placement, which consequently undermines their ability to perform at grade level and on standardized tests. School transfers also decrease the likelihood that a student in foster care will graduate from high school.

Additionally, the frequent moves of youth in foster care often result in delays in enrollment, inappropriate school placements, lack of educational support services, and difficulties in transferring course credits. Excessive school mobility can also impact social development and hinder the foster child’s ability to form and sustain connections and supportive relationships with teachers, counselors, peers and caregivers, all of which are critical to the student’s long term success. The emotional instability that excessive transiency creates can exacerbate behavioral issues, resulting in disciplinary problems (e.g., poor school performance, truancy, fights, substance abuse, etc.). Unfortunately, youth in care often lack a strong advocate to help navigate the obstacles associated with changing schools.

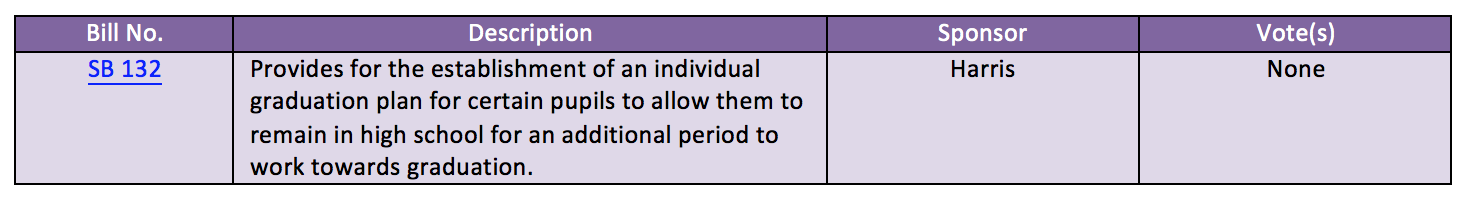

Senate Bill 132

Best Practices in Other States

Louisiana has created a system to help address the challenges of struggling students on the front-end. Students with disabilities and students who are struggling academically are given support and attention in Louisiana through a variety of interventions and programs aimed at keeping these at-risk populations in school and preparing them for college and careers.

Specifically, the Louisiana Department of Education has created an Alternative Jump Start Pathway for students with disabilities to be able to earn a Career Tech Diploma. To be eligible for this pathway, a student must meet one or both of the following criteria: (1) Entering high school having not achieved at least a combination of basic/approaching basic in English and math in two of the three most recent years (6th, 7th, and 8th grades), and/or (2) Does not achieve a score of Fair, Good, or Excellent after two attempts of the same end of course (EOC) test.

Struggling students in Louisiana are typically identified prior to entering high school based on their middle school exam scores. Students that have been designated as non-proficient in English and math are eligible for a transitional ninth grade year, in which a student is placed on a high school campus but provided with services and supports to help the student prepare for secondary-level education courses.