By Meredith A. Levine

Efforts to repeal and replace the Affordable Care Act (ACA) of 2010 have consumed a substantial portion of the legislative agenda of the 115th Congress (2017-2018). One recent proposal, Cassidy-Graham, which is co-sponsored by Nevada’s senior senator, Dean Heller, has garnered renewed interest in modifying the ACA this fall, after a series of measures failed to gain traction over the summer.

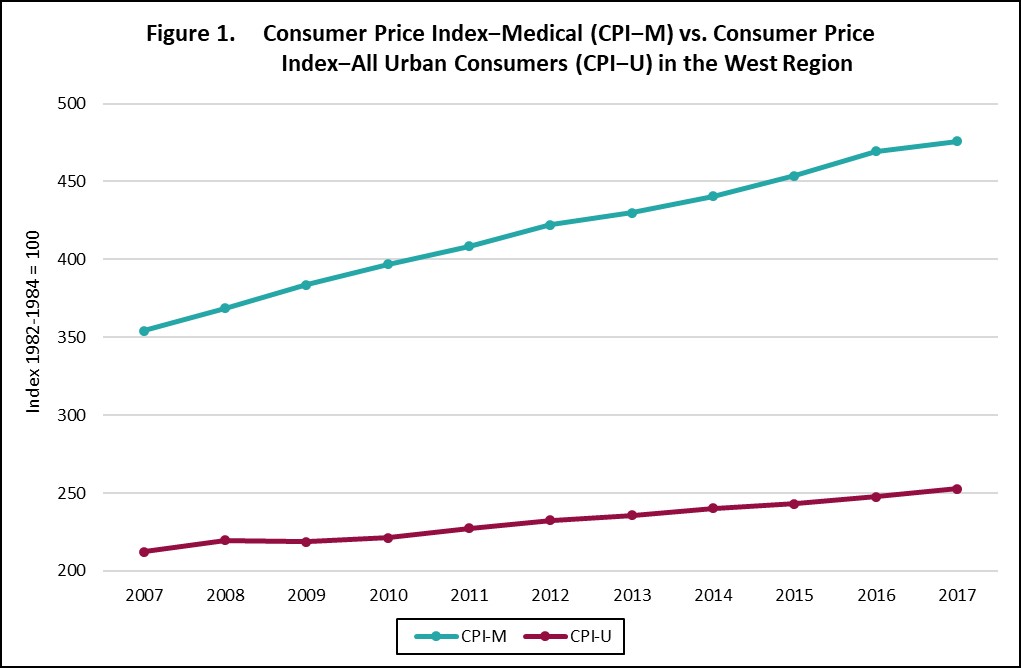

First, some history, as some provisions in Cassidy-Graham bear a striking similarity to those in the now-defunct congressional health care proposals. On May 4, 2017, the U.S. House of Representatives passed H.R. 1628, known as the American Health Care Act (AHCA) of 2017. Amongst its numerous provisions, AHCA would have ratcheted down the Medicaid matching rate for new expansion enrollees to the regular rate by the beginning of 2020; states would have received the enhanced matching rate for previously-enrolled beneficiaries—as of the end of 2019—provided that the enrollees maintained continuous coverage. In addition, AHCA would have restructured Medicaid financing through the introduction of per capita caps on Medicaid spending—set amounts per beneficiary in each state, rather than the current open-ended formula—that would be adjusted for inflation annually using the Medical Consumer Price Index (CPI-M), with the addition of one percentage point per year for the aged and disabled categories. States would have had the option to receive a block grant, instead of a capped amount per year, for which the upside was arguably greater state flexibility over Medicaid spending. The downside, however, was that the block grant would be indexed to the Consumer Price Index for all Urban Consumers (CPI-U), which grows at a lower rate than CPI-M, as shown in Figure 1.

While the U.S. Senate voted to proceed on AHCA, that was a procedural vehicle to open up floor debate, with a Senate bill introduced in the nature of a substitute; senators did not vote on the House-passed legislation itself. The Senate bill was a discussion draft dubbed the Better Care Reconciliation Act (BCRA) of 2017. Like its companion in the House, the Senate legislation contained a myriad of provisions that would have revised the ACA considerably, including the rollback of federal funds to support the Medicaid expansion.

As with the House legislation, BCRA included a per capita cap scheme, or an opt-in provision for a block grant in lieu of capped spending per beneficiary. Unlike AHCA, however, the Senate bill would have imposed a more draconian set of cuts to the per capita cap structure (beginning in FY 2020) via its inflation indexing approach. Specifically, BCRA would have been tied to CPI-M, beginning in FY 2020, and then switched to CPI-U in FY 2025. Similar to AHCA, one percentage point would have been added to CPI-M for most disabled adult enrollees or those aged 65 from FY 2020 through FY 2024. However, unlike the House bill, growth would have been pegged to CPI-U in FY 2025, as with other beneficiaries. In sum, Medicaid financing under the Senate legislation would have followed the contours of the House plan for a five-year period that would have gone into effect later than the House bill. But while the main tenets of the per capita cap scheme in the House-passed legislation did not sunset, once effectuated, similar provisions under BCRA would have been shifted to the CPI-U inflation adjustment.

In late July, BCRA was struck down in the Senate, as were other iterations of repeal, such as the Obamacare Repeal and Reconciliation Act and the Health Care Freedom Act. With Congress set to begin its August recess and a full calendar of exigent actions confronting House members and senators upon their return, including the debt ceiling and funding the government for the next fiscal year, the question of health care reform seemed to be tabled in the immediate short term.

Recently, however, signals out of Washington suggest that, despite the busy congressional calendar—which now includes the imperative of funding for hurricane relief and tax code reform—there is a revival of enthusiasm to modify the ACA. And one plan has remained active: a substitute to H.R. 1628 that was introduced by Senator Lindsey Graham of South Carolina on behalf of himself, Senator Bill Cassidy of Louisiana, and Senator Heller, the day before the final “repeal and replace” vote was called. Given that no action was taken on it in July, there is no need for a new draft of legislation to move forward on discussion and a vote.

The substitute, Senate Amendment (S. Amdt.) 586—or more popularly, Cassidy-Graham, would: (1) repeal the Medicaid expansion (devolving the decision over whether to preserve the expansion to the states), as well as the individual and employer mandates and the medical device tax; (2) retain protections for preexisting conditions; and (3) limit marketplace assistance. In addition, Cassidy-Graham proposes to restructure Medicaid from an entitlement program—whereby “anyone who meets eligibility rules has a right to enroll in Medicaid coverage…[and] states have guaranteed federal financial support for part of the cost of their Medicaid programs”—to an AHCA- or BCRA-like per capita scheme with a block grant option.

In fact, near-verbatim language from BCRA, as it pertains to the per capita cap plan, is integrated into Cassidy-Graham. So, too, is the block grant option. But Section 106 of the amendment also layers another grant atop the per capita cap scheme and/or block grant option, “Short Term Assistance for States and Market-Based Health Care Grant Program,” ostensibly designed to offset some of the immediate losses produced by certain ACA modifications but allowable for a variety of uses. This program allots fixed amounts per annum to the states, beginning in calendar year 2020 and expiring in calendar year 2026, with an approximately 12.9 percent increase over the entire seven-year period. There would be a differential impact across states, as legislatively prescribed parameters, such as states’ per capita income, population density, and Medicaid expansion status, would determine each state’s allotment amount.

In a statement on his decision to join with Senators Cassidy and Graham in sponsoring this version of health care reform, Senator Heller said that, “By allowing states to address the unique health care needs of their populations, it gives states the flexibility to innovate and come up with a tailored approach that is most appropriate for their citizens. In Nevada, this means supporting programs that are currently working in our state and exploring new options to address coverage and cost.”

The short-term assistance program could counterbalance some of the disproportionate effects that the per capita cap scheme would have on Nevada. As observed in our policy brief, “Medicaid Funding in Nevada,” overall, the Silver State spends the least per Medicaid enrollee in the nation. Caps would be based on spending amounts over eight consecutive quarters, but given that they are already low, Medicaid spending would be locked in at potentially insufficient levels to cover costs, even with the inflation adjustments. One recent analysis of the combined effects of the market-based health care grant program and per capita cap scheme under Cassidy-Graham shows that, by 2026, the estimated federal funding change to Nevada would be a loss of $257 million.

By way of example, BCRA may have resulted an additional State contribution of $1.8 billion between 2021 and 2026, though, to be fair, its provisions are not entirely comparable with Cassidy-Graham. Thus, while $257 million is a burden on the State—a bit below the equivalent of the Live Entertainment Tax (LET)–Gaming Tax and Cigarette Tax for the current fiscal year—it is significantly less than what BCRA’s impact would have been on Nevada. And according to the aforementioned analysis, Nevada would fall toward the bottom of hardest-hit states. Based on our ranking of that data, the Silver State would be 35th of all states, as opposed to our Intermountain West neighbor, California, which would be the most deeply affected: that is, the Golden State would rank first, with a loss of $35.2 billion by 2026. The reasons for these differential effects were discussed above, but, in sum, Cassidy-Graham would redistribute federal funds from expansion states to non-expansion states, from states with greater use of marketplace subsidies to lower use of subsidies, from states with higher per capita income to states with lower per capita income, and from states that are more densely populated to those that are less densely populated.

And yet, $257 million is not insubstantial. Nevada’s taxes already finance the State’s programs and operations, so compensation for the loss of federal dollars would mean that the State would need to secure additional revenue streams or make cuts to services, either within the Medicaid program or elsewhere throughout the government, such as to education or public safety.