Nancy Brune and Meredith Levine

Policymakers in Nevada and elsewhere are laser-focused on ways to support and invest in our workforce to spur the pandemic-ravaged economy to return to its full potential. This exercise involves identifying people who are missing and thinking about ways to support them and reimagine a much more inclusive workplace. Women have been the subject of many of these discussions. But as we undertake this exercise, who else is missing? What else can we do? When we asked this question (in our recent 99-page report), it turns out that individuals with intellectual disabilities are largely missing from Nevada’s workforce.

For more than a decade, Nevada has repeatedly stated that integrated employment for individuals with intellectual and/or developmental disabilities (I/DD) is a goal. An executive order has been issued; a task force has been assembled; a strategic plan has been delivered. National and state reforms (e.g., the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act of 2014 and the 700-Hour Program) have imposed new requirements and provided new opportunities to help individuals with differing ability connect to integrated employment.

Furthermore, survey results indicate that many people with intellectual disabilities want a job in the community. Data from the National Core Indicators, a voluntary effort by public developmental disabilities agencies to measure and track their own performance, show that 62 percent of those surveyed in Nevada said they “do not have a paid community job and would like a job in the community.” Despite the stated interest in employment, only 28 percent of the individuals surveyed had “community employment as a goal in their service plan.” And 21 percent indicated that they were taking “classes, training or […] something to get a job or do better at [their] current job.” Of those surveyed in Nevada, 78 percent indicated they had attended a day program or sheltered workshop, which is higher than the national average of 56 percent, and an increase in Nevada from 70 percent in 2015. The survey data aligns with state DHHS data: Roughly 80 percent of individuals with intellectual disabilities receive facility-based services, and facility-based outcomes have increased over the past decade.

And yet, very few individuals with intellectual disabilities in Nevada are employed in integrated settings. In fact, Nevada significantly lags its peer states in the extent to which individuals with I/DD participate in integrated employment.

Of the 189,546 individuals in Nevada aged 18-64 with a disability, about 74,151 have a cognitive or intellectual disability. And of these, roughly 11 percent (or 8,157) likely have a severe or profound disability. States support individuals with intellectual disabilities in four settings: integrated employment, community-based non-work, facility-based work, and facility-based non-work. Integrated employment includes services that are provided in a community setting and involve paid employment of the participant. Community-based non-work is defined as non-job-related supports focusing on community involvement, such as volunteering at a library or museum. Facility-based employment includes “vocational services provided in settings where most people have a disability and receive continuous job-related supports and supervision.” Examples include sheltered work, work activity services, or extended employment programs. Facility-based non-work (also referred to as day habilitation or medical day care programs) includes non-paid services in a setting where most participants have a disability.

In Nevada, there are lots of actors who play a role in helping individuals with disabilities participate in the community and employment. The Nevada Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) Aging and Disability Services Division (ADSD) is the agency of record that funds day and employment services (including waiver-based services). The Department of Employment, Training and Rehabilitation (DETR) Bureau of Vocational Rehabilitation (BVR), often in partnership with community service providers (e.g., Goodwill of Southern Nevada, Capability Health, High Sierra Industries, Opportunity Village, etc.), provides supportive services. Local education agencies also play a critical role in connecting students with disabilities to employment services and post-secondary opportunities before they graduate.

However, our recent report — based on data and extensive interviews with self-advocates, families, and stakeholders — reveals that the system is broken. Seriously broken. Individuals with intellectual disabilities are rarely employed in integrated settings. Worse, integrated employment outcomes have declined in recent years even though state actors have declared integrated employment a goal. This is happening for several reasons, one of which is weak accountability mechanisms, including data reporting and performance management systems.

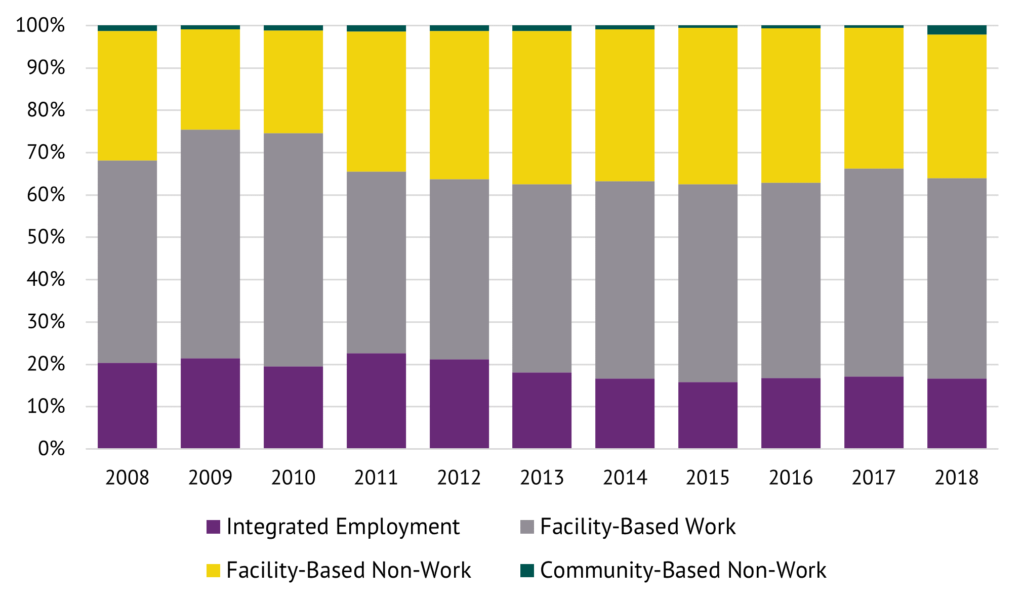

Over the period 2008-2018, the percentage of individuals with intellectual disabilities in Nevada receiving integrated employment services fell from 20 percent to 17 percent (see Figure 1). In stark contrast, facility-based services — both work and non-work — increased over the same period. In 2018, facility-based services (including sheltered workshops) accounted for more than 80 percent of services rendered to individuals with I/DD and 90 percent of total funding.

Figure 1. Percentage Served in Day and Employment Services in Nevada: Service Outcomes, 2008 – 2018

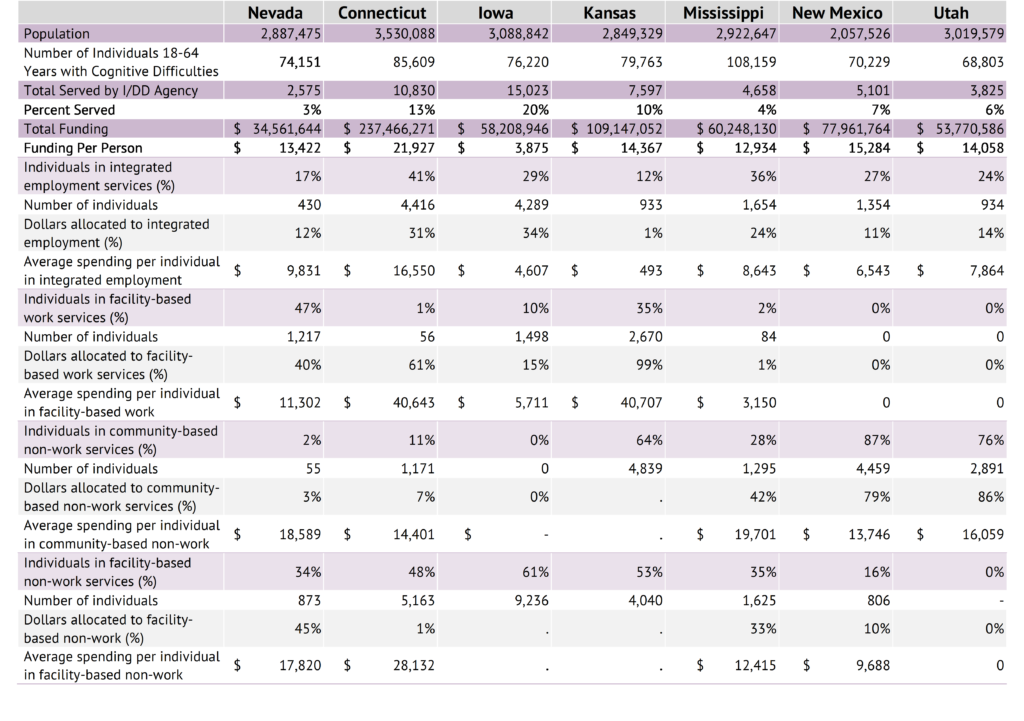

As the table below reveals, Nevada serves fewer individuals with intellectual disabilities than its peer states in day and employment services. In 2018, DHHS ADSD served 2,575 individuals aged 18-64 with cognitive disabilities — or only 3 percent of said population. In contrast, Kansas served 7,597 individuals or 10 percent of its population (aged 18-64) with intellectual disabilities. And Iowa served 15,023 individuals with intellectual disabilities (or 20 percent of its population) in day and employment services.

Table 1. Employment Services for Individuals with Disabilities in Nevada and Peer States, 2018

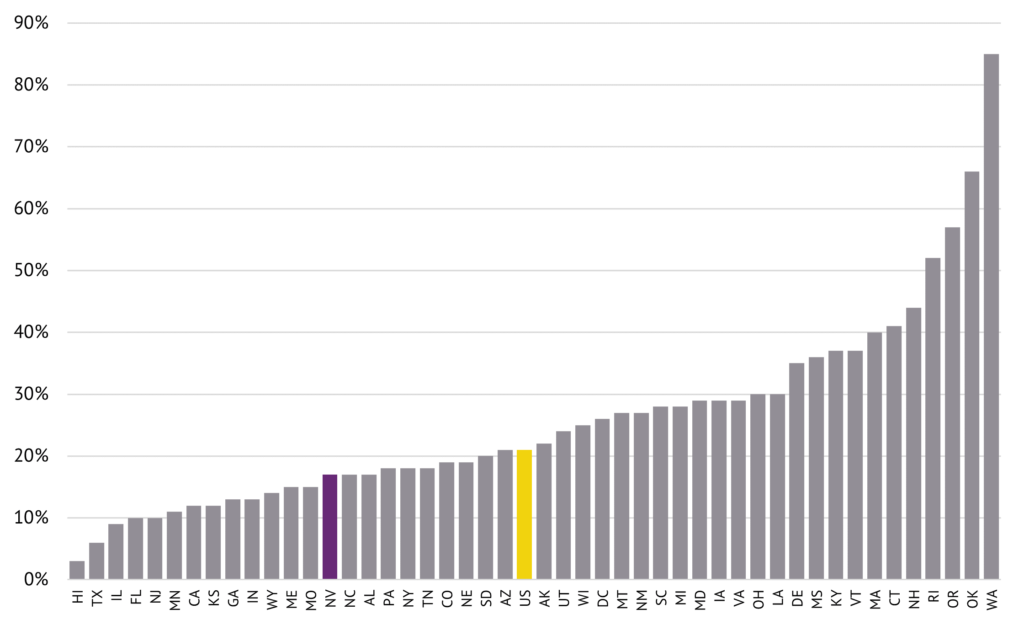

Only 17 percent of Nevada’s population (aged 18-64) with intellectual disabilities has an integrated employment outcome, which is below the national average of 21 percent (see Figure 2). In contrast, 41 percent of Connecticut’s population with I/DD receives integrated employment services.

Figure 2. Integrated Employment Percentage, by State, 2018

Nevada supports individuals with intellectual disabilities who want to participate meaningfully in community life in ways other than employment. But data shows that these sorts of outcomes are significantly limited. In the Silver State, community-based non-work outcomes account for only 2 percent of day and employment service outcomes for individuals with I/DD. In New Mexico and Utah community-based non-work outcomes account for 87 percent and 76 percent respectively.

Nevada’s failure to provide day and employment supports to a greater number of individuals with intellectual disabilities may be attributed to its relatively lower levels of funding. In 2018, Nevada reported the lowest amount of funding: $34.5 million. Connecticut reported the highest level of funding: $237.4 million. Nevada’s regional neighbors, New Mexico and Utah, reported funding levels of $53.7 million and $77.9 million, respectively.

Obviously, honoring or acknowledging person-centered planning means that some individuals with intellectual disabilities may choose to receive services from facility-based settings (or any one of the four settings or some combination thereof). To meet the specific needs and varied interests of individuals with I/DD, Nevada should maintain a balanced portfolio of opportunities. As such, we are not proposing the elimination of any one type of setting.

However, Nevada does not have a balanced portfolio of options: A balanced portfolio is not reflected in a state where facility-based services (including sheltered workshops) account for more than 80 percent of services rendered to individuals with intellectual disabilities, integrated employment outcomes account for only 17 percent, and community-based non-work outcomes account for 2 percent.

Our analysis finds the system is broken in many places. Many parents of students with disabilities have revealed that their children never connected with employment services prior to graduating, despite federal legislation to address this. In 2014, the federal government passed the aforementioned Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act (WIOA), which provides new requirements designed to help “job seekers access employment, education, training, and support services to succeed in the labor market.” Among the new requirements, WIOA prescribes that state vocational rehabilitation agencies and local education agencies provide pre-employment transition services (Pre-ETS). Specifically, under WIOA’s new requirements, state vocational rehabilitation agencies are mandated to set aside at least 15 percent of federal funding (Section 110 grant funds) to provide pre-employment transition services to all students with disabilities who are otherwise eligible for BVR services.

In Nevada, BVR, in collaboration with school districts, must “provide, or arrange for the provision of, pre-employment transition services for all students with disabilities.” These services include job exploration counseling, counseling regarding postsecondary education and training programs, work-based learning experiences, and workplace readiness training. In 2019, BVR sought to provide Pre-ETS services to only 1,898 students (or 23 percent of students with disabilities) and ultimately only provided services to 904 students (or 11 percent of the eligible population). Community and government agency stakeholders shared that “Nevada is really struggling with the delivery of Pre-ETS services.”

Unfortunately, local education agencies shoulder some of the responsibility of a system that is not working for individuals with intellectual disabilities. Special education teams lack knowledge about post-secondary resources. The ability of BVR to get on campus grounds is often the function of a principal’s engagement.

Unfortunately, too, no one is accountable for outcomes. Despite the work of a Task Force and the publication of a strategic plan, integrated employment outcomes have decreased. By and large, Nevada’s individuals with developmental disabilities (particularly young people) are falling through the cracks and no one even knows they are missing from the workforce because accountability systems are missing.

While the Legislature has passed significant reforms in consecutive sessions to improve outcomes for individuals with intellectual disabilities, much more work needs to be done to create a workforce that is inclusive and supports individuals with I/DD who want to pursue integrated employment opportunities.

A summary of our recommendations can be found in our report, Integrated Employment Opportunities for Individuals with Disabilities in Nevada: An Assessment.

(This blog is an excerpt from an opinion piece that originally appeared in The Nevada Independent).