by Niko Centeno-Monroy — Last week, Nevada State Treasurer Dan Schwartz hosted a Payday Loan Summit, which brought together stakeholders around the Silver State to discuss the long term impacts of payday loan debt on consumers in Nevada.

The state summit parallels similar conversations and related efforts nation-wide to address the impact of payday loan debt and explore greater protections for consumers. Earlier this year, Google, the popular web-browsing tech company, announced that the company will be removing all payday loan ads from its search engine effective this summer. While browsers can still “Google” payday loans, the ads themselves will no longer be visible under its ads section when a browser is searching through Google.

Two weeks ago, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) announced that the agency is proposing new rules to protect consumers from debt traps that many payday loan borrowers find themselves in. A debt trap occurs when borrowers cannot pay the initial loan on time and must roll over the loan (incurring additional fees), often more than once. While state law requires payday lenders to limit a consumer’s payback period to 90 days, if a consumer cannot pay back the initial loan within that time period, the lender can issue a new loan that includes incurred fees and interest. According to a CFPB report on payday lending, more than 80 percent of cash-advances are rolled over or followed by another loan within 14 days. The proposed rules “would require lenders to determine whether borrowers can afford to pay back their loans. The proposed rule would also cut off repeated debit attempts that rack up fees and make it harder for consumers to get out of debt. These strong proposed protections would cover payday loans, auto title loans, deposit advance products, and certain high-cost installment loans.” (CFPB is receiving public comment on its proposed rules through September 2016.)

During the Treasurer’s hosted meeting, representatives of various organizations shared information on how payday loans have impacted consumers in Nevada. Nationally, research indicates that groups most likely to use payday loans include: women (between the age of 25 – 44 years old); individuals without a four-year college degree; home renters; African-Americans; individuals earning below $40,000 annually; and individuals who are separated or divorced. Summit participants shared that, in Nevada, senior citizens impacted by the Great Recession, and military personnel and their families also seem to use payday loans at higher rates than the general population. This information echoes a 2015 University of Nevada Las Vegas study that found that “one in five Nevada veterans has used a payday loan, and of those who have taken out a payday loan, half still have payday lending debt, including many who have debt that dates to their time on active duty.”

There was wide-spread agreement among participants that financial literacy, defined as knowledge about money and finances, and education about the various types of financial options and instruments are critical to helping consumers make better financial decisions over the course of their life. At the Financial Guidance Center, a nonprofit that provides financial counseling to Nevadans, it was reported that 80 percent of the organization’s clients that seek help from the center have at least one payday or title loan.

Participants identified important issues for consideration and provided information on policy measures adopted by other states. For example, more than one dozen states have capped payday loan interest rates. This sort of measure could provide some relief for Nevadans. As reported in a 2014 Guinn Center report, average payday loan rates in Nevada are among the highest rates in the Intermountain West (see Table 1).

Table1. Rates on Payday Loans and Regulations to Regulate Payday Lending

| State | Interest Rate+ | Status of Meaningful Legislation to Regulate Payday Lending |

| Arizona | 36 percent* | Has Eliminated the Payday Debt Trap Through APR Limits |

| California | 426 percent | No Meaningful Regulation of Payday Lending |

| Colorado | 214 percent | Has Implemented Reforms that Limit but Do Not Eliminate the Payday Lending Debt Trap |

| Nevada | 521 percent | No Meaningful Regulation of Payday Lending |

| New Mexico | 564 percent | No Meaningful Regulation of Payday Lending |

| Texas | 417 percent | No Meaningful Regulation of Payday Lending |

| Utah | 443 percent | No Meaningful Regulation of Payday Lending |

+ Source: Center for Responsible Lending

* In June 2000, Arizona legalized payday lending by passing an exemption to the state’s interest rate cap on small loans. The exemption was scheduled to sunset in July 2010, at which time payday lenders would only be able to charge a 36 percent APR. Despite the payday lending industry’s efforts to cancel the sunset (through a 2008 ballot measure Proposition 200 “Payday Loan Reform Act”), the sunset went into effect and now payday lenders operating in Arizona can only charge 36 percent.

Possible Policy Solutions

A number of states have implemented various reforms to payday lending services. As the Nevada Treasurer’s Office continues conversations with industry representatives and community stakeholders, the Silver State’s political leaders may want to explore the following policy options, several of which have been implemented around the country.

- Maintain a state-wide database that contains information on the am. The State of Washington has established a state-wide database to which all payday lending licensees are required to report small loans.

- Evaluate the impacts of capping interest rates on payday loans in Nevada. Colorado implemented a series of reforms, one of which was to reduce interest rate fees.

- Evaluate the impacts of limiting the amount of the payday loan in Nevada. Washington limits the amount of the payday loan.

- Limit the number of payday loans a consumer can access during a specific time period. For example, Washington limits payday loan borrowers to eight loans in any twelve-month period from all lenders.

- Require documentation that accurately reflects a consumer’s ability to repay the loan.

- Work with public and private sector leaders to increase the supply of additional financial instruments that meet the needs of financially under-banked or un-banked communities. As policy consultant Kevin Kimble noted in a recent American Banker edition, the CFPB’s proposed rule, will have no effect on improving the supply of “quality of credit products” or “small-dollar lending alternatives” for the underserved. Kimble notes, “While we wait for the CFPB’s rules to be formally released, lawmakers and other regulators should begin now to focus on creating a coherent policy to increase the number of quality credit products.

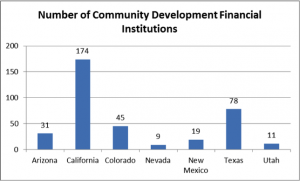

The lack of small dollar lending alternatives is a stark reality here in Nevada. For example, Nevada has one of the lowest penetration rates of community development financial institutions compared to its Intermountain West peers (see Figure 1). Community development financial institutions (CDFIs) – including community banks and community credit unions — can provide additional financial resources to communities, individuals, and entrepreneurs. According to the U.S. Treasury, CDFIs “provide a unique range of financial products and services in economically distressed target markets, such as: mortgage financing for low-income and first-time homebuyers and not-for-profit developers; flexible underwriting and risk capital for needed community facilities; and technical assistance, commercial loans and investments to small start-up or expanding businesses in low-income areas.”

Critics and supporters of payday lending services acknowledge that these lenders provide a service to consumers who are not able to access traditional financial institutions. As such, the portfolio of policy solutions that Nevada’s political leaders are exploring in consultation with industry stakeholders and community groups should include efforts to increase the number and types of available sources of credit that meet the needs of underbanked populations.

Figure1. Community Development Financial Institutions